• 简介

• 体外分化巨噬细胞的M1 /M2范例

• 体外分化小胶质细胞的M1 /M2范例

• M1/M2模型在体内有效吗?

• 产品

• 参考文献

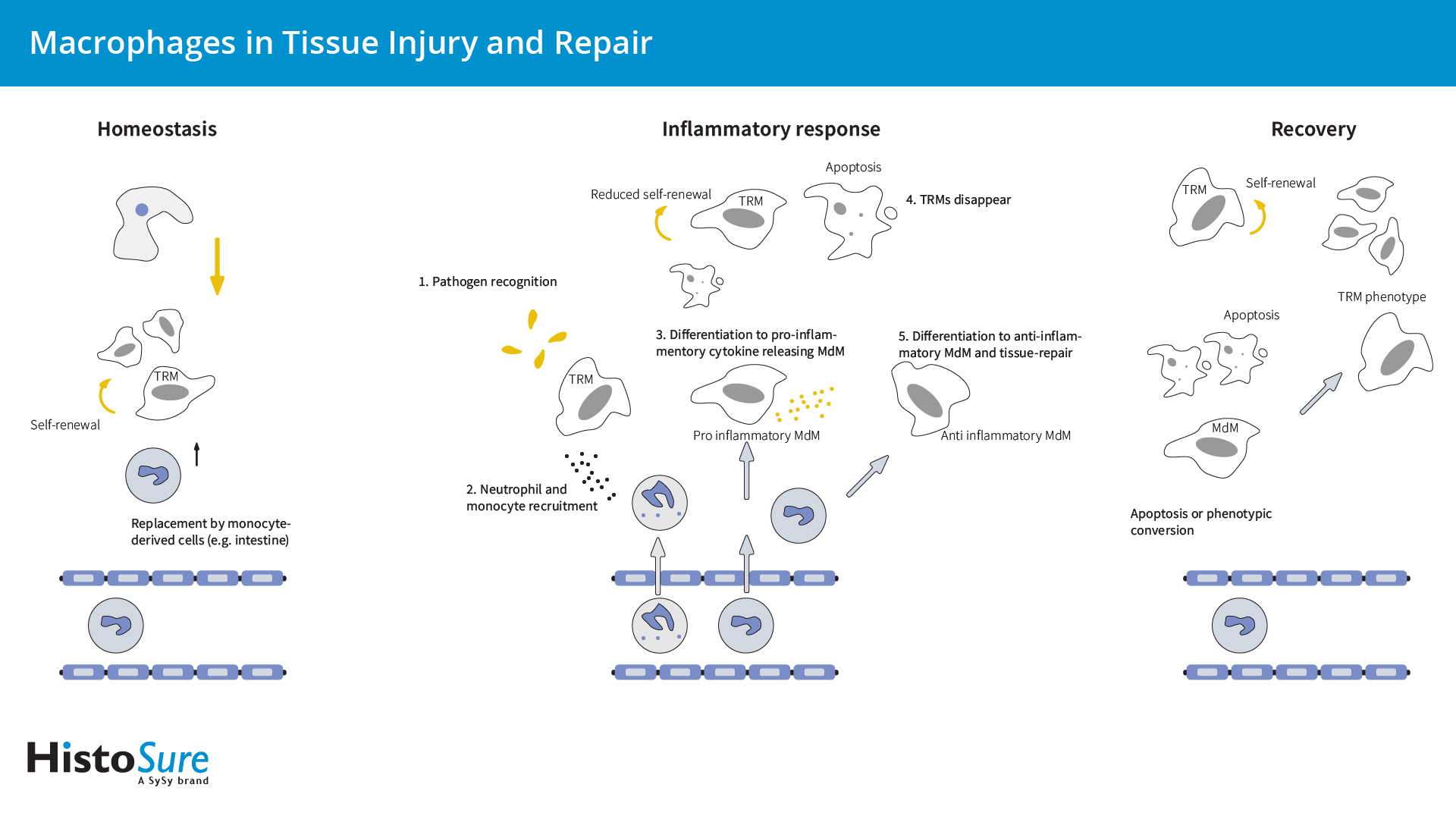

巨噬细胞是普遍存在于所有哺乳动物组织中的一种骨髓细胞异质群,它们根据自身的位置和基因表达谱执行不同的任务,并参与炎症的启动和终止。组织驻留巨噬细胞(TRMs)通常起源于胚胎卵黄囊或胎肝前体,并可通过自我更新来维持其数量(图1)。巨噬细胞一旦发育,就会受到其特定环境的影响,可以接受多种表型和激活状态。例如,肝脏中的库普弗细胞主要参与废物处理,而肺中的肺泡巨噬细胞则是抵御吸入病原体的第一道防线。相反,血液单核细胞来源的巨噬细胞对维持组织内驻留巨噬细胞仅有很小的帮助。而肠道是一个例外,它含有大量的血液单细胞来源的驻留巨噬细胞(Italiani et al., 2014)。中枢神经系统(CNS)包含四种巨噬细胞。小胶质细胞遍布整个大脑,在中枢神经系统的发育和成熟中发挥作用,并形成大脑的主要防线。血管周围巨噬细胞、脑膜巨噬细胞和脉络膜丛巨噬细胞战略性地位于中枢神经系统屏障,从而支持对抗外部抗原的屏障功能(Li and Barres, 2018)。

若想了解小鼠组织驻留巨噬细胞的功能,请见小鼠组织驻留巨噬细胞

图1:组织驻留巨噬细胞(TRMs)和单细胞来源的巨噬细胞(MdMs)在组织损伤和修复中扮演着不同的角色。TRMs起源于胚胎卵黄囊或胎肝前体,并可通过自我更新维持它们的数量。少数TRMs 来源于血单核细胞。TRMs在组织稳态中根据其位置不同而执行不同的任务。TRMs和 MdMs在组织损伤时发挥不同的作用:TRMs 涉及组织损伤的初始识别,而 MdMs表现出更 强烈的炎症反应。在组织损伤恢复期间,TRMs可增强自我更新和重新填充组织生态位。而MdMs 仅对重新填充有微弱作用。

在炎症反应中,对感染或组织损伤的初始识别是由TRMs介导的,TRMs具有多种识别病原体受体或危险相关的分子模式(图1)。因此,TRMs可被激活并产生中性粒细胞趋化因子,例如CXCL1、CXCL2或单核细胞趋化蛋白-1 (MCP-1)(Kumar et al., 2018)。在第一波炎症中,中性粒细胞会迁移到炎症部位,引发第二次炎症反应,从而吸引单核细胞和巨噬细胞(Kumar et al., 2018)。血液单核细胞可通过CCL2/CCR2或CX3CR1途径募集,这些细胞中的绝大多数可生成炎症性单核细胞来源的巨噬细胞(MdMs) (Italiani et al., 2014)。由于组织会通过引流淋巴管迁移、细胞死亡(Davies et al., 2013)以及急性炎症期间自我更新能力降低,因而激活的TRM种群会迅速减少(Mu et al.,2021)。在炎症的早期阶段,巨噬细胞通过清除凋亡细胞和向T淋巴细胞呈递抗原而启动先天免疫。成功的急性炎症反应可导致感染因子的根除,并伴随着由抗炎巨噬细胞引发的组织修复(Lee和Choi 2018)。抗炎巨噬细胞通常在初始损伤后第三天出现,它们要么源于促炎巨噬细胞,经历了表型转换,要么源于血液单核细胞(Bohaud et al., 2021)。在恢复过程中,TRMs通过增加局部增殖而重新填充炎症组织,同时由于细胞死亡,浸润MdMs减少(Davies et al., 2013, Mu et al., 2021)。少数招募的MdMs持续存在,其中一些可获得自我更新能力,并经历缓慢的原位表型转化成为TRMs (Watanabe et al., 2019; Mu et al., 2021)。过度或未解决的巨噬细胞激活可导致致病性慢性炎症,如动脉粥样硬化、糖尿病、多发性硬化症和肌萎缩侧索硬化症。

为更好地描述巨噬细胞功能,根据刺激类型、表面分子表达、细胞因子分泌和功能特征,可将巨噬细胞和小胶质细胞分为M1或M2。这种极化命名法是在2000年根据辅助性T细胞(Th)的Th1 / Th2概念引入的(Mills et al., 2000)。

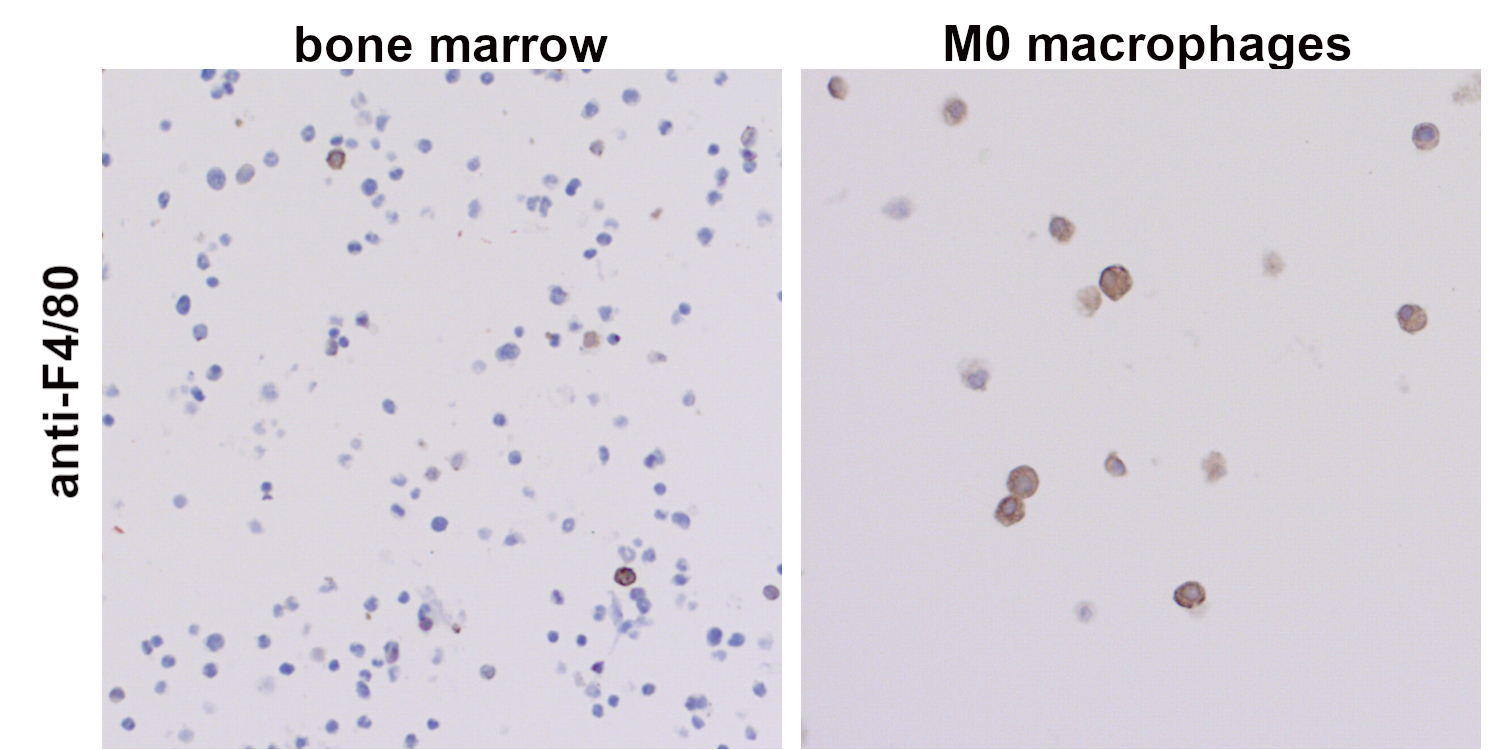

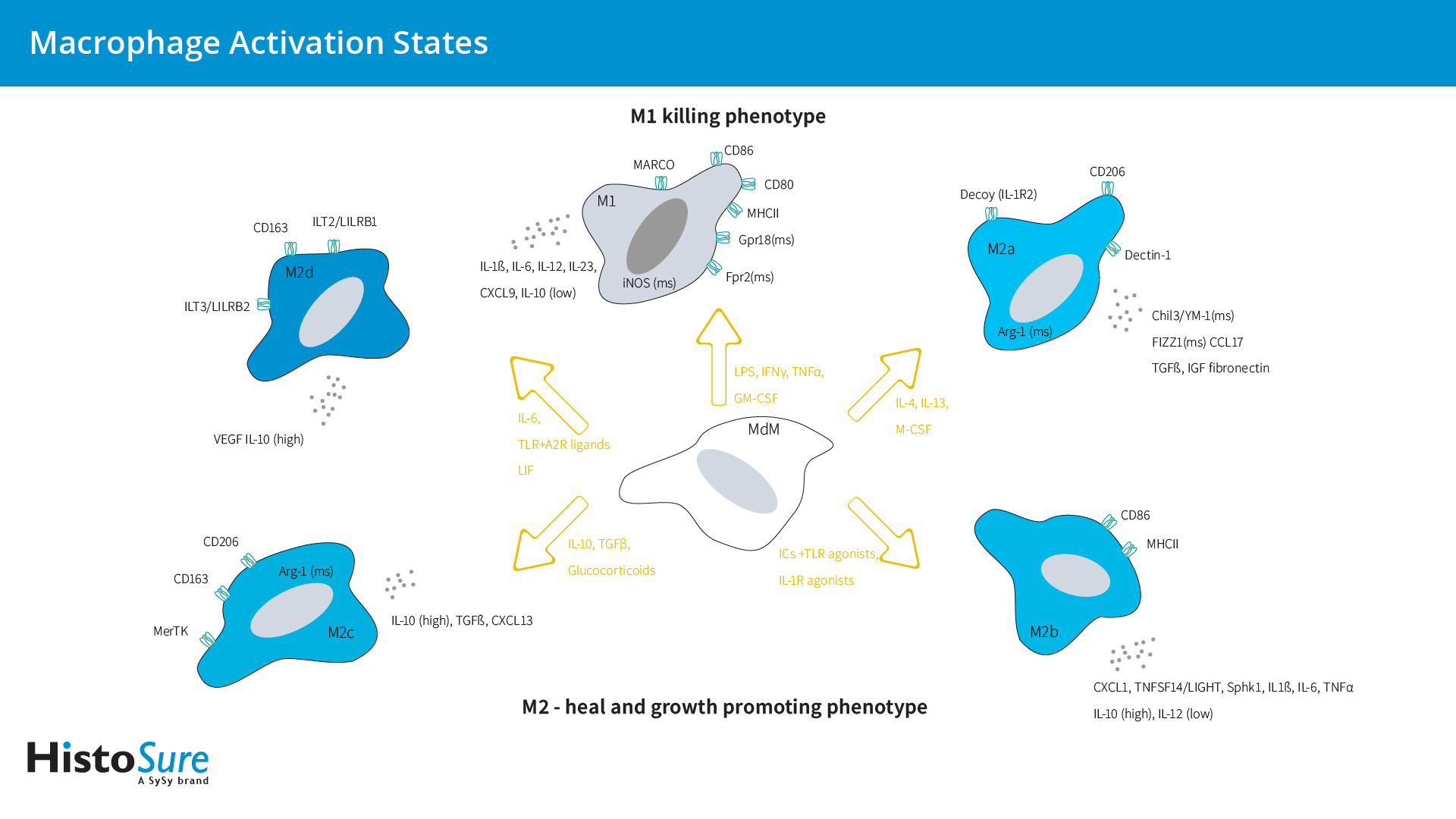

来自血液、骨髓或脾脏的单核细胞可以在体外分化为巨噬细胞(M0)(图2)。在响应不同环境刺激时,巨噬细胞可以采取促愈合/生长(M2巨噬细胞)或杀伤表型(M1巨噬细胞)(图5)。

图 2:在巨噬细胞集落刺激因子(M-CSF)存在时,小鼠骨髓细胞可分化为巨噬细胞。采集的小鼠骨髓细胞和分化的巨噬细胞,经福尔马林固定和石蜡包埋,使用抗-F4/80 (HS-397 017,稀释倍数 1:100; DAB)抗体染色。细胞核由苏木精染色可见为蓝色。在未培养的小鼠骨髓中,F4/80阳性的细胞不到10%(左)。在成熟过程中,F4/80的表达增加,且体外分化的M0巨噬细胞表达高水平F4/80(右)。

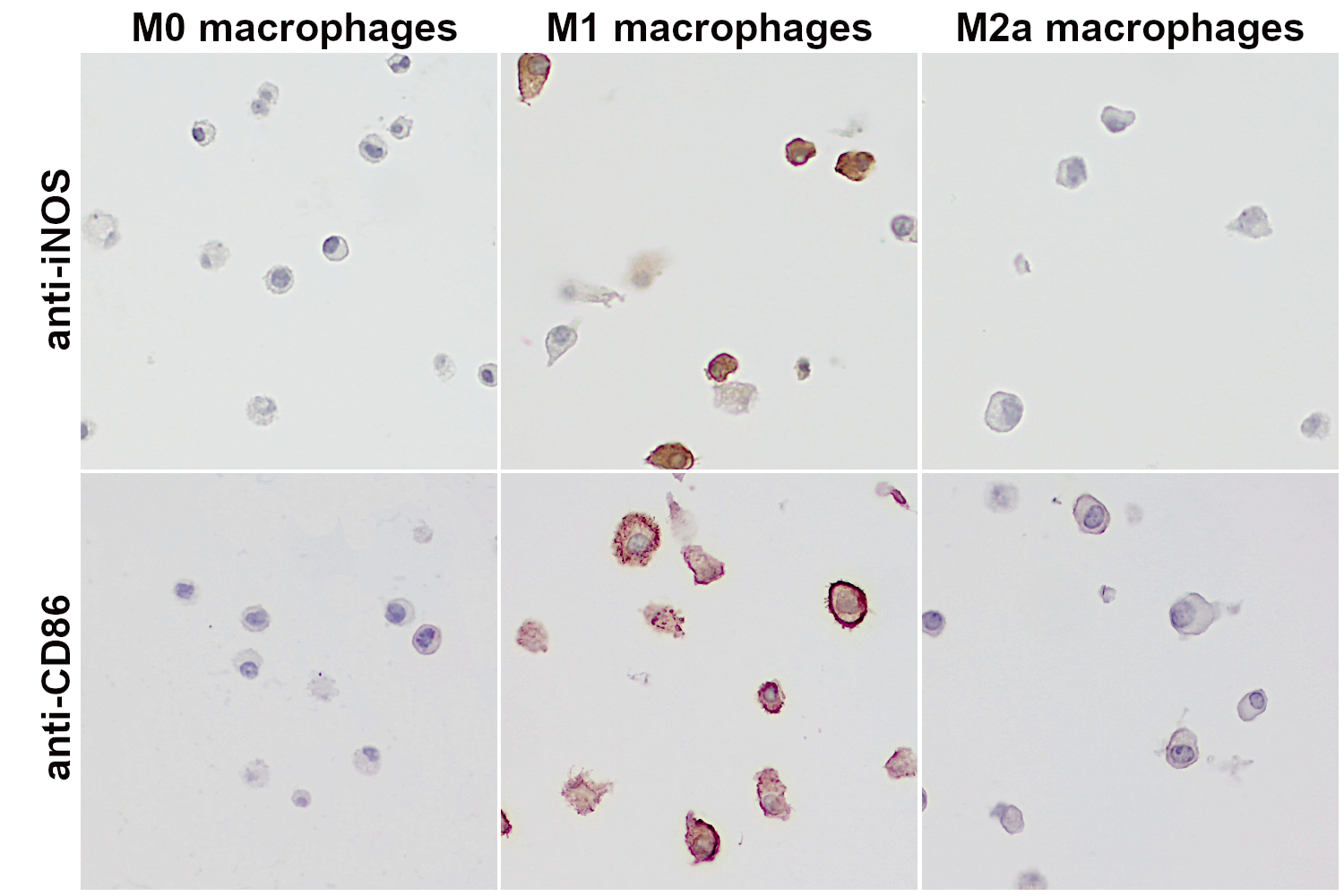

经典活化M1巨噬细胞是在体外响应Th1细胞产生的细胞因子干扰素-γ(IFNγ)和肿瘤坏死因子- α (TNFα)或微生物产物如脂多糖(LPS)形成的(图3)。M1表型的特点是抗原呈递能力高,可产生一氧化氮(NO)、趋化因子配体9 (CXCL9)和白细胞介素IL-12和IL-23。小鼠M1巨噬细胞可通过表达CD38、G蛋白偶联受体18 (Gpr18)和甲酰基肽受体2 (Fpr2)而进行鉴定(Jablonski et al., 2015)。LPS也会引起清除受体MARCO(具有胶原结构受体的巨噬细胞)的上调(Chen et al., 2010),该受体在摄取肿瘤细胞中发挥了关键作用(Xing et al., 2021)。

图 3:小鼠巨噬细胞可被刺激分化为M1或M2a样表型。为得到M1样表型细胞或M2a样表型细胞,细胞分别用LPS + IFNγ或IL-4处理12 - 18小时。刺激物可直接添加进培养基中,而对照细胞(M0巨噬细胞)的培养基中则未添加刺激物。孵育结束后,分化后的巨噬细胞会被收集,随后由福尔马林固定,石蜡包埋。细胞的成功分化则使用不同的标记物来监测。第一行:使用大鼠抗iNOS(cat. no. HS-484 017, 1:5000; DAB)抗体进行免疫组化染色。在IFNγ和LPS处理下分化的M1巨噬细胞中可检测到iNOS的高表达。第二行:使用兔抗CD86 (cat. no. HS-466 003, 1:1000; DAB)抗体进行间接免疫染色。在IFNγ和LPS作用下分化的M1巨噬细胞中可检测到CD86的高表达。

作为寄生虫防御的效应物,选择性活化的M2巨噬细胞具有多种功能,具有免疫调节特性,可促进肿瘤生长和侵袭性,并协调组织修复和重塑(Lee and Choi, 2018)。而用于定义巨噬细胞极化的M1/M2模型则主要识别连续体的极端,但不能反映M2巨噬细胞的功能异质性。因此,M2巨噬细胞可进一步细分为M2a、M2b、M2c和M2d亚型(Mantovani et al., 2004; Ferrante et al., 2012) (图5)。

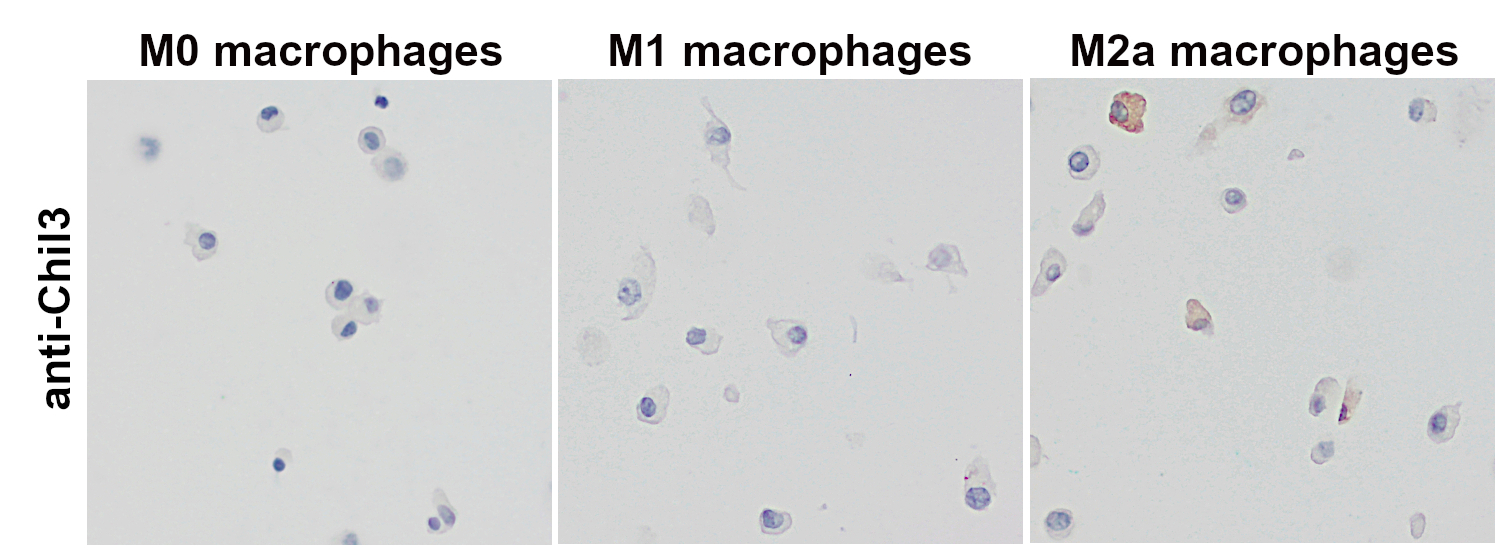

在这一分类中,M2a亚型代表了典型的IL-4 / IL-13依赖亚型,参与了凋亡细胞的清除、促炎反应的调节以及伤口愈合。M2a巨噬细胞可高表达甘露糖受体(CD206)、诱饵IL-1受体(IL-1R2)和CCL17,并分泌促纤维化因子。然而,人和小鼠巨噬细胞在极化标记物的表达上存在显著差异。鉴定小鼠M2a巨噬细胞的可靠标记物由Chil3 (YM-1)(图4)、Arg1和FIZZ1 (Raes et al., 2002; Ferrante 2012),但这些基因没有人类同源物。此外,Dectin-1/CLEC7A (Willment et al., 2003)、早期生长反应蛋白2 (Egr2)和c-Myc也被认为是小鼠M2a特异性基因(Jablonski et al., 2015)。转谷氨酰胺酶2 (TGM2)是人类和小鼠中一个独特的功能保守的M2a标记物(Martinez et al., 2013)。

图 4:使用大鼠抗-Chil3/YM-1 (cat. no. HS-442 017,稀释比例 1:1000; DAB)抗体,对经福尔马林固定、石蜡包埋的体外分化小鼠巨噬细胞的细胞沉淀物进行免疫组化染色。在选择性激活的M2a巨噬细胞中可检测到Chil3表达。细胞核可被苏木精染色可见为蓝色。

M2b巨噬细胞,又名为调节性巨噬细胞,可通过联合暴露于免疫复合物(ICs)和TLR激动剂或IL-1R激动剂而被诱导。M2b巨噬细胞可高度表达共刺激分子,是高效的抗原呈递细胞。M2b巨噬细胞可以通过鞘氨酸激酶1 (Sphk1)和LIGHT/TNFSF14的表达来识别(Edwards et al., 2006)。

巨噬细胞的抗炎M2c亚型(“获得性失活巨噬细胞”)是由IL-10通过激活信号传感器和转录激活因子3 (STAT3)而诱导产生的(Wang et al., 2018)。M2c巨噬细胞可表达Mer酪氨酸激酶(MerTK),这使得M2c巨噬细胞比其他巨噬细胞亚型在清除凋亡细胞时效率更高(Zizzo et al., 2012)。

血管生成型M2d亚型是由腺苷依赖性M1巨噬细胞的“开关”而产生的。M2d亚型的特点是促炎细胞因子的释放减少,而IL-10和强效血管生成分子血管内皮生长因子(VEGF)上调(Ferrante et al., 2012)。这种亚型也被称为肿瘤相关巨噬细胞(TAM),代表着肿瘤组织中主要的炎症成分(Duluc et al., 2007)。TAMs具有强大的免疫抑制功能,较低的抗原递呈能力,可通过分泌趋化因子配体CCL17、CCL22和CCL18而促进Tregs、Th2细胞和初始T细胞的募集。白血病抑制因子(LIF)和IL-6是肿瘤微环境因子,可促进血源性单核细胞生成TAM (Duluc et al., 2007)。在LIF和IL-6存在时,人体巨噬细胞会分化表现出CD14high、CD163high、CD80low、CD86low、ILT2high、和ILT3high表型(Duluc et al., 2007)。

图5:巨噬细胞激活状态概述。该图罗列出了主要的激活表型、获得这些表型所用刺激物、以及与不同激活表型相关的标记物。

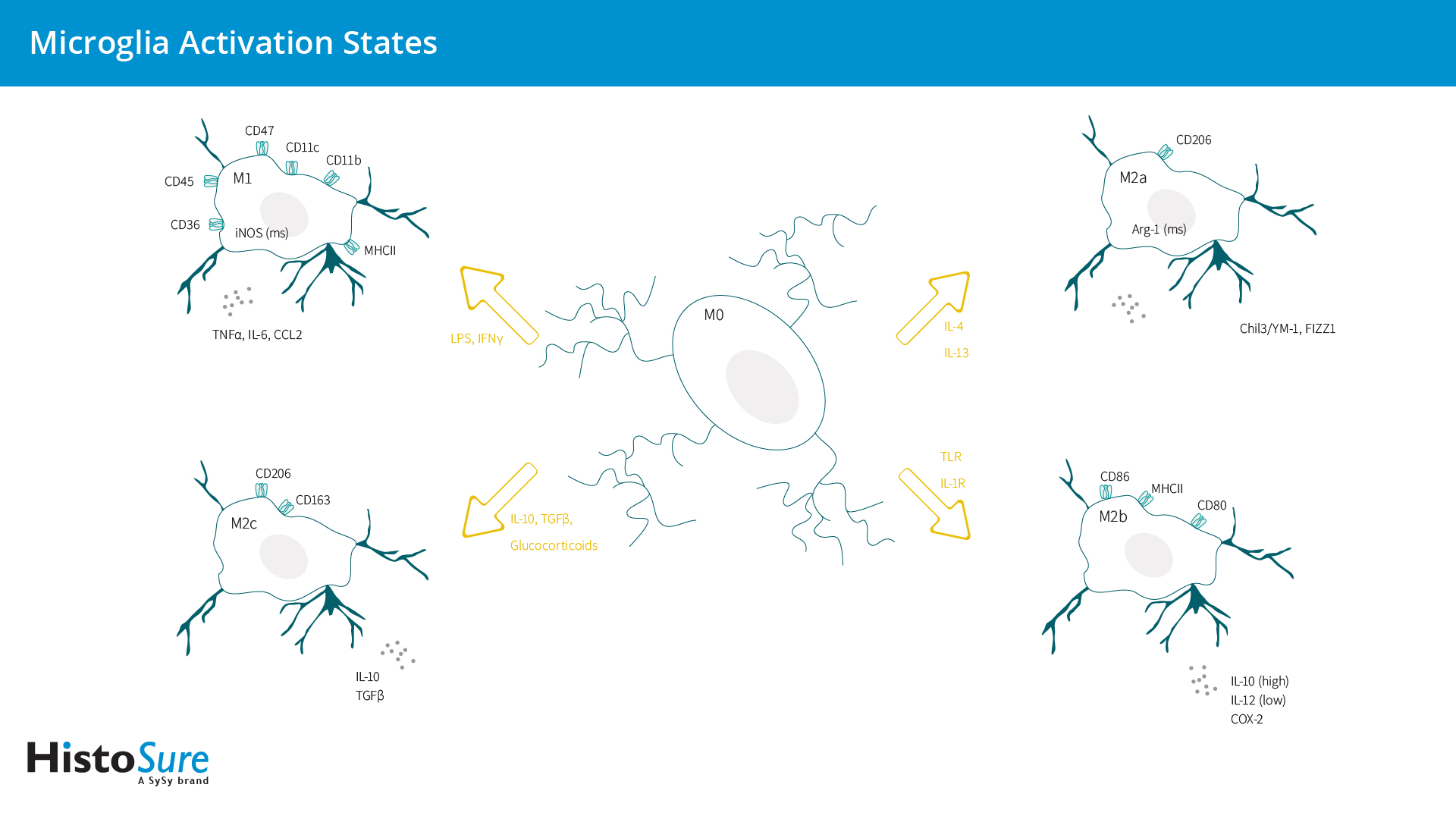

传统上认为,小胶质细胞在生理条件下处于静止的M0状态,而在病理条件下会被激活。与巨噬细胞类似,小胶质细胞在响应不同微环境刺激时可分化为促炎M1表型或抗炎M2表型(图6)。

在体外,M1小胶质细胞在干扰素γ (IFNγ)或脂多糖(LPS)存在下会进行分化。M1小胶质细胞主要分泌促炎细胞因子,如肿瘤坏死因子α (TNFα)、白细胞介素-6 (IL-6)和IL-12,并可通过表达烟酰胺腺嘌呤二核苷酸磷酸(NADPH)氧化酶和诱导型NO合成酶(iNOS)而产生活性氧(ROS)和一氧化氮(NO)。M1小胶质细胞可高度表达MHCII、CD86、CD40和Fcγ受体(CD16/CD32),从而实现抗原呈递、整合素(CD11b和CD11c)和共刺激分子(CD36、CD45、CD47)(Colonna and Butovsky, 2017; Zhou et al., 2017)。M1小胶质细胞可诱导炎症和神经毒性。

与巨噬细胞类似,M2状态表征抗炎表型和愈合小胶质细胞表型,并可进一步细分为选择性活化M2a,过渡性活化M2b和获得性失活的M2c状态(Colonna and Butovsky, 2017)。M2a表型参与寄生虫免疫和组织修复,并产生抗炎细胞因子。M2b表型与M1小胶质细胞具有相同的特征,并可表达M1相关的细胞表面蛋白CD86和MHCII (Wendimu and Hooks, 2022)。M2c小胶质细胞介导清除髓磷脂碎片并参与髓鞘再生。与Wnt5a分泌M1小胶质细胞相反,M2c小胶质细胞分泌大量Wnt7a (Mecha et al., 2020) (表2)。

图6:小胶质细胞激活状态概述。该图罗列出了主要的激活表型、获得这些表型所用刺激物、以及与不同激活表型相关的标记物。

| 激活 | 细胞标记物 | 分泌蛋白 | |

| M1 | IFN-γ LPS |

NADPH oxidase iNOS MHCII CD86 CD11b CD11c CD36 CD45 CD47 CD16/32 CD40 |

TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β, IL-12, CCL2 IL-12/IL-23 CCL5/CCL11 MMP12 Wnt5a |

| M2a | IL-4 IL-13 |

CD206 Arg-1 (小鼠) |

Chil3/YM-1 (小鼠) FIZZ1 (小鼠) |

| M2b | TLR IL-1R |

MHCII CD86 |

IL-10 (高), IL-12 (低) COX-2 |

| M2c | IL-10 glucocorticoids TGF-β |

CD163 CD206 Arg-1 (小鼠) |

TGFβ IL-10 Wnt7a |

巨噬细胞和小胶质细胞在体内能轻易地分为M1和M2吗?答案很简单:不能。

M1/M2模式是一种基于用一组特定因子刺激培养中的巨噬细胞、小胶质细胞或细胞系的体外模型。根据M1/M2模型,组织常驻巨噬细胞通常被归类为类M2。然而,体外实验结果已很难进行比较。在体外实验中,常见巨噬细胞极化标记物的表达受到产生巨噬细胞的细胞类型的强烈影响,例如,单核细胞系或来自血液或骨髓的原代细胞。小胶质细胞和TRMs受其组织环境的强烈影响,培养的腹膜巨噬细胞和小胶质细胞在7天的孵育期后完全失去了其组织特异性基因表达程序(Gosselin et al., 2014)。此外,体内巨噬细胞分化也会被不同的培养条件(Wang et al., 2022)和刺激持续时间(Purcu et al., 2022)而显著影响。特定巨噬细胞极化标记物的最佳刺激时间差异很大,会导致假阴性结果,使得不同研究间的比较更加困难(Purcu et al., 2022)。体外环境和分化细胞所用的刺激,例如M-CSF和GM-CSF,可在巨噬细胞被刺激到M1或M2表型之前就启动并激活。GM-CSF在LPS刺激后可导致更促炎的状态(TNF表达),而M-CSF会诱导为组织愈合状态(IL-10表达)(Orecchioni et al., 2019)。

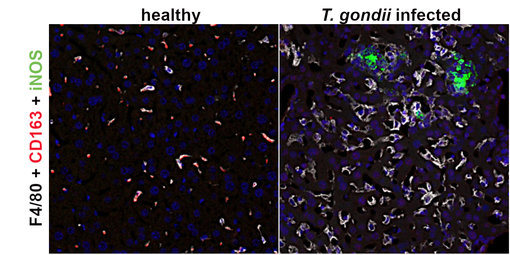

图7:使用在酰胺信号放大(TSA)法,对未感染(健康)和感染弓形虫的小鼠肝脏进行以下荧光检测: F4/80 (HS-397 004, 1:1000; 白色)、 CD163 (HS-455 003, 1:500, 红色) and iNos (HS-484 017, 1:1000; 绿色)。CD163和F4/80在健康小鼠肝脏中共定位于大的库普弗巨噬细胞中。在受感染的肝脏中,巨噬细胞失去了CD163 表达。在肝细胞坏死灶中检测到了诱导型一氧化氮(iNOS)。

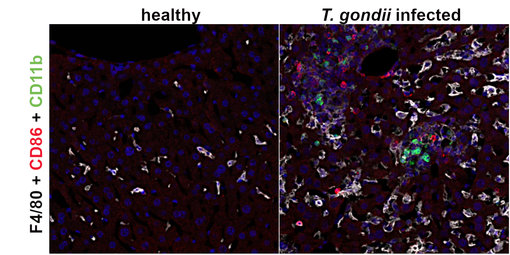

图8:使用在酰胺信号放大(TSA)法,对未感染(健康)和感染弓形虫的小鼠肝脏进行以下荧光检测:F4/80 (HS-397 017, 1:250; 白色)、 CD86 (HS-466 003, 1:500, 红色) 和CD11b (HS-384 308, 1:1000; 绿色)。在健康小鼠肝脏中都未检测到CD86和 CD11b阳性细胞。在受感染的肝脏中,在位于或靠近肝细胞坏死灶中检测到了CD11b阳性单核细胞和CD86表达细胞。

在体内,巨噬细胞存在于M1/M2二分亚型之外,并可以表达M1和M2亚型的标记物(Oates et al., 2022)。巨噬细胞极化比二元制M1和M2模型更为复杂,M1和M2状态仅代表光谱的极端。M2巨噬细胞仍能表达M1标记物,但表达程度低于M1巨噬细胞,反之亦然(Boutilier and Elsawa, 2021)。在体内,LPS处理的巨噬细胞与体外分化的巨噬细胞一样,仅可调控少数基因,且有些基因和通路调控甚至是相反的。这可能是由于在体外研究中使用了未成熟的巨噬细胞前体,例如骨髓,而这些前体在外周组织中并没有检测到(Orecchioni et al., 2019)。

小胶质细胞是中枢神经系统的第一道防线,必须持续接收来自周围细胞的“一切正常”信号,以维持免疫监视。当轻度损伤发生时,损伤部位的细胞会发出“找我”信号,从而使得小胶质细胞迅速进入M2状态。M2小胶质细胞具有远端分支和小细胞体样改变的特点,可促进细胞组织修复和再生。如果组织发生严重或持续损伤,细胞则会发出“吃我”信号,从而激活小胶质细胞为具有厚突起的变形虫或圆形细胞体状态–促炎或毒性M1表型。

然而,M1/M2的命名法对在体内条件下的描述过于简单。即使在没有感染的情况下,如创伤或缺血再灌注后,小胶质细胞也会在体内分化。这表明了替代刺激的存在(Wang et al., 2023)。全基因组表达谱研究强调了小胶质细胞表型的复杂性,在衰老和病理疾病模型中显示了混合M1/M2表型。而在例如创伤性脑损伤(TBI)或视网膜变性的小鼠模型中也观察到过渡性表型 (Wendimu and Hooks, 2022)。在急性炎症反应中,活化的小胶质细胞表现出上调CD11b、ICAM-1、P-选择素、主要组织相容性复合体II (MHCII)、CD80 (T细胞共刺激分子B7-1)、CD86 (T细胞共刺激分子B7-2)和CD40(肿瘤坏死因子(TNF)受体成员)的特征(Lima et al., 2022)。半乳糖凝集素-3 (Gal-3)仅在活化的小胶质细胞中表达(图9),是神经退行性疾病中调节小胶质细胞活化的新靶点(Garcia-Revilla et al., 2022)。

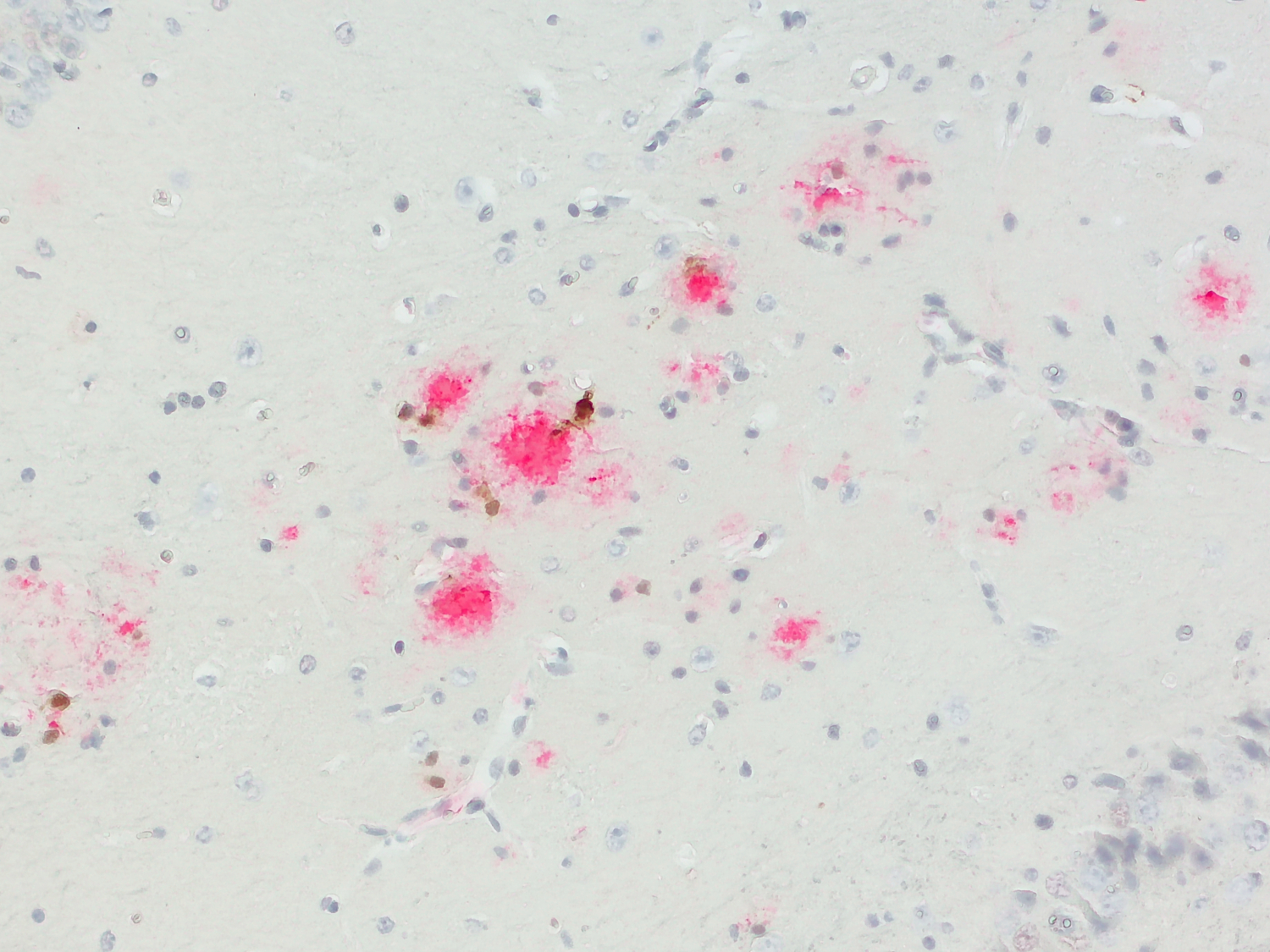

图9:半乳糖凝集素-3 (Cat. HS-477 017, 1:1000; DAB; 棕色)和Abeta38/40/42/43 (Cat. 218 008, 1:1000; AP-RED; 红色)在阿尔茨海默病小鼠模型(APP PS1)中的显色双染色。表达半乳糖凝集素-3 的活化小胶质细胞位于Aβ斑块附近。细胞核用苏木精染色可见为(蓝色)。

在稳态下,由于大脑特异性区域差异,小胶质细胞已经表现出不同的表型特征(Böttcher et al., 2019)。此外,小胶质细胞多样化在早期发育和衰老过程中表现出性别差异,并在响应疾病病理中表现出不同的亚群(Tremblay 2021)。目前,已提出几种小胶质细胞亚型,分别命名为“卫星”小胶质细胞:位于神经元细胞体轴突侧;角蛋白硫酸盐阳性的KSPG小胶质细胞:位于运动神经元周围;CD11c小胶质细胞:位于新生小鼠体内;Hoxb8阳性小胶质细胞;“支持神经发生的小胶质细胞”和“暗”小胶质细胞(已在 Wang et al., 2023中评述)。

综上所述,巨噬细胞和小胶质细胞不能简单地分为M1和M2、善与恶、或者丑与美。相反,谱系似乎包括所有可能的M1/M2混合表型。

| Cat. No. | Product Description | Application | Quantity | Price | Cart |

|---|

HS-500 003 | Arg-1, rabbit, polyclonal, affinity purifiedaffinity C-terminal | WB IHC IHC-P | 50 µg | US$375.00 | |

HS-500 013 | Arg-1, rabbit, polyclonal, affinity purifiedaffinity N-terminal | WB IHC IHC-P | 50 µg | US$375.00 | |

HS-384 008 | CD11b, rabbit, monoclonal, recombinant IgGrecombinant IgG mouse specific | WB IHC IHC-P IHC-Fr | 100 µl | US$420.00 | |

HS-384 017 | CD11b, rat, monoclonal, purified IgG IgG human specific | WB IHC-P | 200 µl | US$420.00 | |

HS-384 018 | CD11b, rabbit, monoclonal, recombinant IgGrecombinant IgG human specific | WB IHC-P | 100 µl | US$420.00 | |

HS-384 103 | CD11b, rabbit, polyclonal, affinity purifiedaffinity mouse specific | WB ICC IHC IHC-P | 200 µl | US$455.00 | |

HS-384 117 | CD11b, rat, monoclonal, purified IgG IgG mouse specific | WB IHC IHC-P IHC-Fr | 200 µl | US$420.00 | |

HS-384 117BT | CD11b, rat, monoclonal, purified IgG IgG, biotin mouse specific | WB IHC-P | 100 µg | US$470.00 | |

HS-384 308 | CD11b, Guinea pig, monoclonal, recombinant IgGrecombinant IgG mouse specific | WB IHC IHC-P IHC-Fr | 100 µl | US$420.00 | |

375-0P | CD11c, control peptidecontrol peptide | 100 µg | US$110.00 | ||

HS-375 003 | CD11c, rabbit, polyclonal, affinity purifiedaffinity mouse specific | WB IHC IHC-P | 200 µl | US$375.00 | |

HS-375 004 | CD11c, Guinea pig, polyclonal, antiserumantiserum mouse specific | WB IHC IHC-P | 100 µl | US$355.00 | |

HS-375 008 | CD11c, rabbit, monoclonal, recombinant IgGrecombinant IgG mouse specific | IHC IHC-P | 50 µg | US$420.00 | |

HS-375 017 | CD11c, rat, monoclonal, purified IgG IgG mouse specific | IHC IHC-P IHC-Fr | 100 µg | US$420.00 | |

HS-455 003 | CD163, rabbit, polyclonal, affinity purifiedaffinity mouse specific | WB IHC IHC-P | 200 µl | US$375.00 | |

HS-455 004 | CD163, Guinea pig, polyclonal, antiserumantiserum mouse specific | IHC IHC-P | 100 µl | US$355.00 | |

HS-455 013 | CD163, rabbit, polyclonal, affinity purifiedaffinity human specific | IHC-P | 50 µg | US$375.00 | |

HS-455 014 | CD163, Guinea pig, polyclonal, antiserumantiserum human specific | IHC-P | 100 µl | US$355.00 | |

HS-495 017 | CD169, rat, monoclonal, purified IgG IgG mouse specific | IHC IHC-P | 100 µg | US$420.00 | |

HS-495 111 | CD169, mouse, monoclonal, purified IgG IgG human specific | IHC IHC-P | 100 µg | US$420.00 | |

HS-488 003 | CD206, rabbit, polyclonal, affinity purifiedaffinity | WB ICC IHC IHC-P | 50 µg | US$375.00 | |

HS-488 005 | CD206, Guinea pig, polyclonal, affinity purifiedaffinity | WB IHC IHC-P | 50 µg | US$420.00 | |

HS-493 017 | CD39, rat, monoclonal, purified IgG IgG mouse specific | WB IHC IHC-P | 100 µg | US$420.00 | |

HS-493 117 | CD39, rat, monoclonal, purified IgG IgG human specific | ICC IHC-P | 100 µg | US$420.00 | |

HS-427 003 | CD45, rabbit, polyclonal, affinity purifiedaffinity human specific | WB ICC IHC-P | 50 µg | US$375.00 | |

HS-427 008 | CD45, rabbit, monoclonal, recombinant IgGrecombinant IgG mouse specific | IHC IHC-P IHC-Fr | 100 µl | US$420.00 | |

HS-427 017 | CD45, rat, monoclonal, purified IgG IgG mouse specific | IHC IHC-P IHC-Fr | 200 µl | US$420.00 | |

HS-427 117 | CD45, rat, monoclonal, purified IgG IgG human specific | IHC-P | 100 µg | US$420.00 | |

HS-460 003 | CD68, rabbit, polyclonal, affinity purifiedaffinity | WB IHC IHC-P | 50 µg | US$375.00 | |

HS-460 004 | CD68, Guinea pig, polyclonal, antiserumantiserum | IHC IHC-P | 100 µl | US$355.00 | |

HS-460 008 | CD68, rabbit, monoclonal, recombinant IgGrecombinant IgG human specific | WB IHC-P | 100 µl | US$420.00 | |

HS-460 017 | CD68, rat, monoclonal, purified IgG IgG human specific | WB ICC IHC-P | 200 µl | US$420.00 | |

HS-466 003 | CD86, rabbit, polyclonal, affinity purifiedaffinity mouse specific | WB IHC IHC-P IHC-Fr | 50 µg | US$375.00 | |

HS-442 008 | Chil3, rabbit, monoclonal, recombinant IgGrecombinant IgG mouse specific | WB IHC IHC-P | 50 µg | US$420.00 | |

HS-442 017 | Chil3, rat, monoclonal, purified IgG IgG mouse specific | WB ICC IHC IHC-P | 100 µg | US$420.00 | |

HS-442 117 | Chil3, rat, monoclonal, purified IgG IgG mouse specific | WB ICC IHC IHC-P | 100 µg | US$420.00 | |

HS-501 003 | CLEC4F, rabbit, polyclonal, affinity purifiedaffinity C-terminal | WB IHC IHC-P | 50 µg | US$375.00 | |

HS-501 017 | CLEC4F, rat, monoclonal, purified IgG IgG C-terminal | WB IHC IHC-P | 100 µg | US$420.00 | |

HS-501 103 | CLEC4F, rabbit, polyclonal, affinity purifiedaffinity N-terminal | WB IHC IHC-P | 50 µg | US$375.00 | |

HS-516 003 | CX3CR1, rabbit, polyclonal, affinity purifiedaffinity | WB ICC IHC IHC-P | 50 µg | US$375.00 | |

HS-397 004 | F4/80, Guinea pig, polyclonal, antiserumantiserum | IHC IHC-P | 100 µl | US$355.00 | |

HS-397 008 | F4/80, rabbit, monoclonal, recombinant IgGrecombinant IgG | WB IHC IHC-P | 100 µl | US$420.00 | |

HS-397 017 | F4/80, rat, monoclonal, purified IgG IgG | WB IHC IHC-P IHC-Fr | 200 µl | US$420.00 | |

HS-397 017BT | F4/80, rat, monoclonal, purified IgG IgG, biotin | WB IHC-P | 100 µg | US$470.00 | |

HS-477 008 | Galectin-3, rabbit, monoclonal, recombinant IgGrecombinant IgG mouse specific | WB IHC IHC-P | 50 µg | US$420.00 | |

HS-477 017 | Galectin-3, rat, monoclonal, purified IgG IgG K.O. mouse specific | WB IHC IHC-P IHC-Fr | 100 µg | US$420.00 | |

HS-477 017BT | Galectin-3, rat, monoclonal, purified IgG IgG, biotin mouse specific | WB IHC-P | 100 µg | US$470.00 | |

HS-477 103 | Galectin-3, rabbit, polyclonal, affinity purifiedaffinity | WB ICC IHC-P | 50 µg | US$355.00 | |

HS-234 008 | IBA1, rabbit, monoclonal, recombinant IgGrecombinant IgG | WB ICC IHC IHC-P | 100 µl | US$425.00 | |

HS-234 013 | IBA1, rabbit, polyclonal, affinity purifiedaffinity K.O. | WB IHC IHC-P | 200 µl | US$385.00 | |

HS-234 017 | IBA1, rat, monoclonal, purified IgG IgG | WB ICC IHC IHC-P | 200 µl | US$420.00 | |

HS-234 017BT | IBA1, rat, monoclonal, purified IgG IgG, biotin | WB IHC-P | 100 µg | US$470.00 | |

HS-234 308 | IBA1, Guinea pig, monoclonal, recombinant IgGrecombinant IgG | WB ICC IHC IHC-P | 50 µg | US$430.00 | |

HS-484 008 | iNOS, rabbit, monoclonal, recombinant IgGrecombinant IgG mouse specific | WB IHC-P | 50 µg | US$420.00 | |

HS-484 017 | iNOS, rat, monoclonal, purified IgG IgG mouse specific | WB IHC-P | 100 µg | US$420.00 | |

HS-499 003 | MARCO, rabbit, polyclonal, affinity purifiedaffinity mouse-specific | WB IHC IHC-P | 50 µg | US$375.00 | |

| End of List |

Kumar et al., 2018. Partners in crime: neutrophils and monocytes/macrophages in inflammation and disease. PMID: 29387942

Italiani et al., 2014: From Monocytes to M1/M2 Macrophages: Phenotypical vs. Functional Differentiation. PMID: 25368618

Davies et al., 2013. Tissue-resident macrophages. PMID: 24048120

Bohaud et al. The Role of Macrophages During Mammalian Tissue Remodeling and Regeneration Under Infectious and Non-Infectious Conditions. PMID: 34335621

Li and Barres, 2018. Microglia and macrophages in brain homeostasis and disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 18, 225-242. PMID: 29151590

Lee and Choi, 2018. Macrophages and Inflammation. https://doi.org/10.4078/jrd.2018.25.1.11

Mills et al., 2000. M-1/M-2 macrophages and the Th1/Th2 paradigm. PMID: 10843666

Jablonski et al., 2015. Novel Markers to Delineate Murine M1 and M2 Macrophages. PMID: 26699615

Chen et al. 2010. A regulatory role for macrophage class A scavenger receptors in TLR4-mediated LPS responses. PMID: 20162551

Xing et al., 2021. Scavenger receptor MARCO contributes to macrophage phagocytosis and clearance of tumor cells. PMID: 34626585

Mantovani et al., 2004. The chemokine system in diverse forms of macrophage activation and polarization. PMID: 15530839

Ferrante et al., 2012. Regulation of Macrophage Polarization and Wound Healing. PMID: 24527272

Raes et al., 2002. FIZZ1 and Ym as tools to discriminate between differentially activated macrophages. PMID: 12892049

Willment et al., 2003. Dectin-1 expression and function are enhanced on alternatively activated and GM-CSF-treated macrophages and are negatively regulated by IL-10, dexamethasone, and lipopolysaccharide. PMID: 14568930

Jablonski et al., 2015. Novel Markers to Delineate Murine M1 and M2 Macrophages. PMID: 26699615

Martinez et al., 2013. Genetic programs expressed in resting and IL-4 alternatively activated mouse and human macrophages: similarities and differences. PMID: 23293084

Edwards et al., 2006. Biochemical and functional characterization of three activated macrophage populations. PMID: 16905575

Wang et al., 2018. M2b macrophage polarization and its roles in diseases. PMID: 30576000

Zizzo et al., 2012. Efficient Clearance of Early Apoptotic Cells by Human Macrophages Requires M2c Polarization and MerTK Induction. PMID: 22942426

Duluc et al., 2007. Tumor-associated leukemia inhibitory factor and IL-6 skew monocyte differentiation into tumor-associated macrophage-like cells. PMID: 17848619

Colonna and Butovsky, 2017. Microglia Function in the Central Nervous System During Health and Neurodegeneration. PMID: 28226226

Zhou et al., 2017. Microglia Polarization with M1/M2 Phenotype Changes in rd1 Mouse Model of Retinal Degeneration. PMID: 28928639

Wendimu and Hooks, 2022. Microglia Phenotypes in Aging and Neurodegenerative Diseases. PMID: 35805174

Mecha et al., 2020. Involvement of Wnt7a in the role of M2c microglia in neural stem cell oligodendrogenesis. PMID: 32192522

Gosselin et al., 2014. Environment Drives Selection and Function of Enhancers Controlling Tissue-Specific Macrophage Identities. PMID: 25480297

Wang et al., 2022. CCL22-Polarized TAMs to M2a Macrophages in Cervical Cancer In Vitro Model. PMID: 35805111

Purcu et al., 2022. Effect of stimulation time on the expression of human macrophage polarization markers. PMID: 35286356

Orecchioni et al., 2019. Macrophage Polarization: Different Gene Signatures in M1(LPS+) vs. Classically and M2(LPS–) vs. Alternatively Activated Macrophages. PMID: 31178859

Oates et al., 2022 Characterizing the polarization continuum of macrophage subtypes M1, M2a and M2c. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.06.13.495868

Boutilier and Elsawa, 2021. Macrophage Polarization States in the Tumor Microenvironment. PMID: 34209703

Wang et al., 2023. A richer and more diverse future for microglia phenotypes. PMID: 37025898

Wendimu and Hooks, 2022. Microglia Phenotypes in Aging and Neurodegenerative Diseases. PMID: 35805174

Lima et al., 2022. Microglial Priming in Infections and its Risk to Neurodegenerative diseases. PMID: 35783096

Garcia-Revilla et al. 2022: Galectin-3, a rising star in modulating microglia activation under conditions of neurodegeneration. PMID: 35859075

Böttcher et al., 2019 Human microglia regional heterogeneity and phenotypes determined by multiplexed single-cell mass cytometry. PMID: 30559476

Tremblay, 2021. Microglial functional alteration and increased diversity in the challenged brain: Insights into novel targets for intervention. PMID: 34589793